Trending

4 Considerations To Craft Your Company’s Equity Strategy

/in Talent, Featured on Home, Equity & Compensation, Trending, I Need to Retain my Top Performers, Developing Your Team, Secondary Liquidity/by Matt McCueAdvancing Your Influence: Strategies for CFOs

/in Leadership & Vision, CFO Leadership, Developing Your Team, Featured on Home, Trending, Talent/by Matt McCueHow People Leaders Can Invest In Their Own Growth

/in Featured on Home, Trending, Talent, I Need to Retain my Top Performers, Developing Your Team, Leadership & Vision/by Matt McCueShare this entry

How New Tax Law Impacts Startup Equity: New Rules Could Make it Easier for Employees to Exercise Options

Countless workers have been hit with surprise tax bills after they exercise options, the result of Internal Revenue Service rules that haven’t always been friendly to startups.

The good news is that the new tax law offers relief for some employees who might otherwise have been forced to hold options or let them expire because of a large tax bill.

Peter Klinger, a principal in the compensation and benefits practice at BDO, has been advising startups on tax issues for more than 25 years. We spoke to him recently about the new law and what implications the new AMT tax bill has for startups and their employees.

The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What’s the biggest change for option holders?

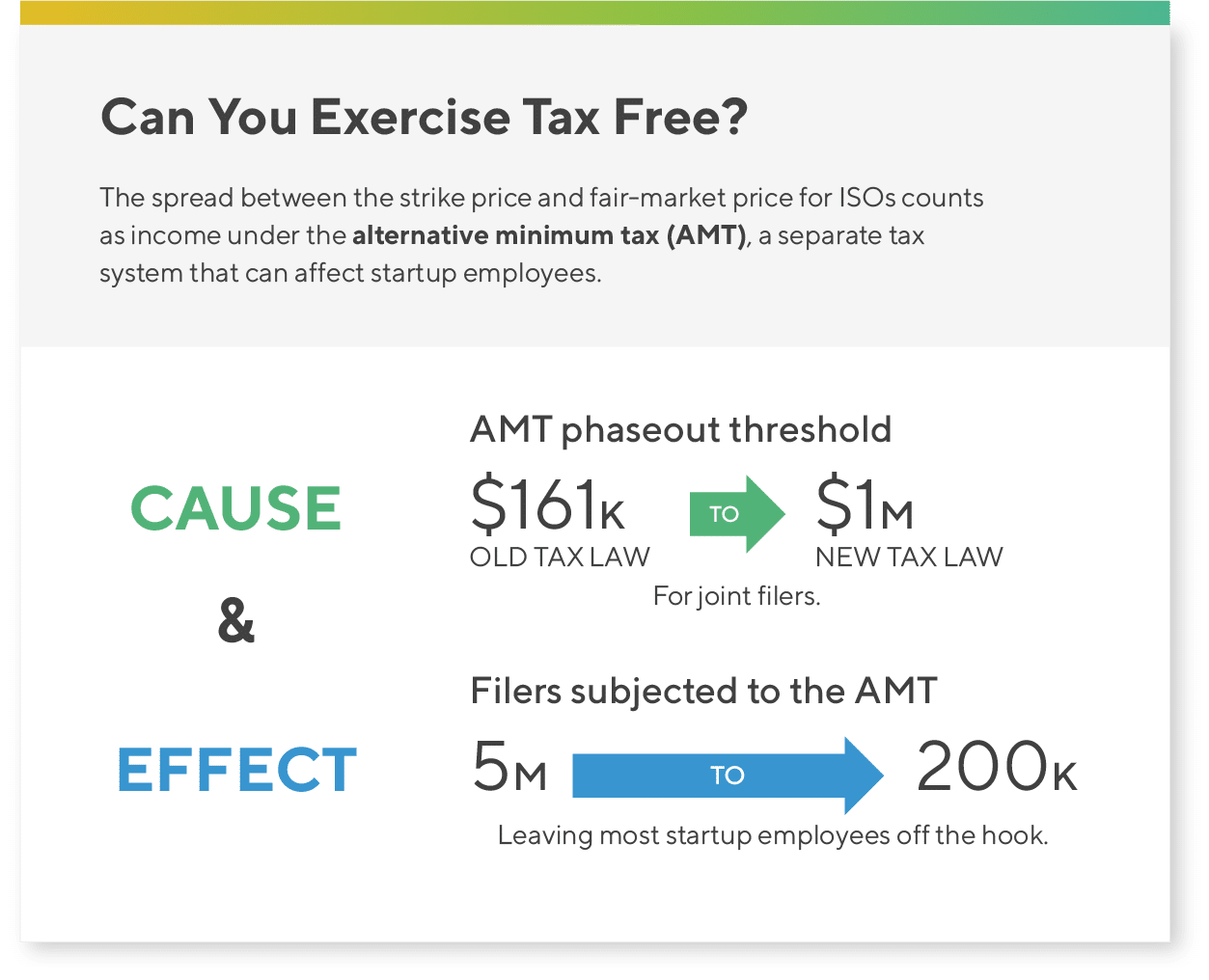

The biggest change is on the individual income tax side related to the alternative minimum tax (AMT). The AMT is a parallel set of tax rules that were enacted in 1969 to capture more revenue from very high net worth individuals. Prior to the passage of the tax reform law, the AMT was expanded to a point where a lot of folks that aren’t high-net-worth individuals were impacted as well.

The biggest change is on the individual income tax side related to the alternative minimum tax (AMT). The AMT is a parallel set of tax rules that were enacted in 1969 to capture more revenue from very high net worth individuals. Prior to the passage of the tax reform law, the AMT was expanded to a point where a lot of folks that aren’t high-net-worth individuals were impacted as well.

When you exercise an incentive stock option (ISO), assuming you don’t sell the shares in the same calendar year, there’s no impact on your regular income tax. But the spread between the strike price and the fair market value at the time of exercise is included as income in the formula that determines AMT. So, if you already owe the AMT, then you’re going to pay tax on the spread. If you’re not subject to the AMT, exercising may put you there.

Following tax reform, the AMT threshold is higher and after-income phaseouts may also be significantly higher, which means fewer people will have to pay taxes when they exercise. That could help them lock in long-term capital gains. However, behavior has to follow suit: Employees have to exercise and hold their stock, which in the past, very few have done.

Did the AMT affect a lot of startup employees?

Let’s just say there’s a complicated history. Back in the dot-com days, startups granted ISOs to employees as much as they could. Many of these employees didn’t understand the workings of AMT. I used to do a lot of seminars back in those days, and I’d ask the audience, “How many people have heard of AMT?” And maybe one or two out of 30 or 40 hands would go up.

During the dot-com boom, employees would exercise at a time when stock prices or valuations were very high, but would not sell or were not able to sell. Then the market crashed, and their stock was worth next to nothing. But their tax bill stayed the same because it was set at the time of exercise. The result was a large number of employees with a huge tax bill and no way to pay it.

There’s a new section in the tax code that seems to relate to startups called 83(i). What is it?

Section 83(i) is intended to allow employees to defer paying tax on stock awards for up to five years, although there are events like an IPO that would cause employees to owe the tax sooner. In theory, an employee could exercise early, and then not have to pay the tax bill until there’s a liquidity event, avoiding the problem some face now.

It’s well-intentioned, but I don’t really see 83(i) as practical because of the way it’s set up. First, it’s a broad-based plan in which the stock options (or RSUs) must be offered to essentially all full-time1 employees with the “same rights and privileges”—rather unclear language when it comes to implementation. Second, deferral elections may be made by the rank-and-file employees, while the top executives (CEO, CFO, four highest-paid officers, and more-than-1 percent owners) cannot defer taxes on their options. But if a company repurchased stock in a prior year not connected with an 83(i) election, as many companies did, then they would be precluded from offering these plans in the current year, in most cases.

83(i) also has a lot of administrative requirements for employers, which might be enough of a burden for them to choose not to bother offering a plan. Every year, employers would need to report for each employee the amount includible in income at the end of the 83(i) deferral period and the aggregate amount of income being deferred under 83(i) elections at the close of each year2. Further, the company must notify the employees at the time the stock option is exercised or a reasonable time before. The company is liable for a penalty of $100 for each required notice they fail to provide. They would also have to attach forms to their corporate tax returns that would include summaries of all the amounts that they reported on W-2s.

Complying with these requirements would be a significant undertaking for a small private company.

Are there other problems with 83(i)?

Employees usually sell their stock awards as soon as they can. Here, you’re asking them to do the opposite, essentially deferring to pay the tax, holding the shares, and then paying a (presumably) lower amount of tax later. However, you run the risk of repeating the problem from the dot-com boom, as employees may not be able to sell until the value of the shares has already declined. If the value of the shares drops from the date they exercise, they still owe the tax on the amount that was due at the time of exercise.

And then there’s the FICA (Federal Insurance Contribution Act) problem. If I exercise an ISO as part of an 83(i) plan, it immediately becomes a non-qualified stock option, which doesn’t change its value but does change the way it’s treated under the tax code. For tax purposes, unlike ISOs, the spread between the strike price and fair-market value for non-qualified stock options count as ordinary income. Section 83(i) allows employees to defer paying income tax, but not FICA tax, which includes Social Security and Medicare. So the employee and the employer will both owe FICA at the time that the election is made.

There’s one other problem, too. The tax deferral ends on the date of an IPO. So employees would owe the tax on any options they exercised under 83(i) that day. It’s the employer’s responsibility to collect and remit the tax payments to the IRS, also that day. But there’s no liquidity at that point because the employees can’t sell their stock for another six months. So, how is the company going to collect and remit the tax payment?

Facebook faced a similar problem when it went public. Vested RSUs were due to employees at the IPO. That was a taxable event, except those employees, couldn’t sell the stock right away because they were subject to a six-month lockup. Facebook had to go to the bank and take out billions of dollars in loans to pay the tax on behalf of the employees, who then repaid those loans when the six-month lockup period had ended.

With all these headaches, it’s hard to see many companies deciding to offer 83(i) programs.

What’s stayed the same in this law?

The $100,000 limit with respect to ISO hasn’t changed. You can only get options that qualify as ISOs to the extent that in any calendar year, the strike price multiplied by the number of shares that become first exercisable in that year is $100,000 or less. Once you exceed that number, then those automatically become non-qualified stock options, which, as I mentioned earlier, are taxable as ordinary income upon exercise.

Also, there’s a lot of gray area in the tax code around equity compensation that the language of the new law didn’t clarify. And it’s unclear if or when the IRS will shed light on these details. The agency is facing severe resource constraints and has publicly said they’re prioritizing other issues at this time.

What would you recommend startups do?

The smartest thing startups can do is have a plan for how to treat equity well in advance of any possible liquidity event, and to make sure employees understand the tax impact of exercising options.

Companies should also take the time to determine whether an 83(i) plan is right for them, but as I said earlier, they need to consider the potential administrative burden before moving forward. The new tax law is complicated, and changes in one area can have a ripple effect throughout the tax liability of both companies and individuals.

A startup’s equity tax implications can be difficult to foresee, but great care must be taken to understand changes to AMT in order to create the best possible equity program for an organization. Mapping out the impact of these changes is critical to informing any tax strategy moving forward.

2§§ 6051(a)(16),(17).

Related Blog Posts

4 Considerations To Craft Your Company’s Equity Strategy

Evolving Your Compensation Plan on the Road to IPO